Ritual and Social Drama Among The Qashqai

Manouchehr Shiva*

Below, I review anthropological studies of ritual among the pastoral nomadic/tribal communities in Iran, and provide my own ideas about different rituals among the Qashqai. By relying on works of Victor Turner and Catherine Bell, I emphasize looking at political conflicts as social dramas, or ritualized processes, through which various forms of tribal, ethnic, national, class, and gender identities are constructed, imposed, resisted, negotiated, and reconstructed.

There is a tendency of “mthodolgical nationalism” implicit in viewing ritualized practices among the Qashqai in the framework of works on other tribal/pastoral nomadic communities in Iran. This methodological nationalist tendency was, and still is, dominant in anthropological literature, co-existing withe a “methodolgical regionalism” (e. g., the Middle East region).

Ritual and the Middle Eastern Pastoral Nomadic Tribal Communities

Barth’s (1961) study of the Basseri tribe of Fars introduced a new genre of studies on pastoral nomadic tribes in the Middle East in which the topics of ritual and the related concepts of the religious, the symbolic, and the meaningful were underemphasized. A variety of factors might have influenced such neglect. There were the cultural peculiarities of the Basseri, and many other pastoral nomadic tribes in the Middle East, who did not emphasize the practice of public Islamic rites, or at least the way these rites were practiced in urban and urban-dominated rural communities. There were the peculiarities of anthropological research of the time, practiced in a context of limits posed by theoretical perspectives (in this case what is usually called “cultural ecology”), and personalities. There was a definition bias, based on strict delineation of the sacred and the profane that central to the emergence of social anthropology as a discipline. There was also a Durkheimian propensity, again central to traditional social anthropology, by which researchers searched for rituals representing structural cohesion of the groups, as opposed to practices that represented and reconstructed conflict.

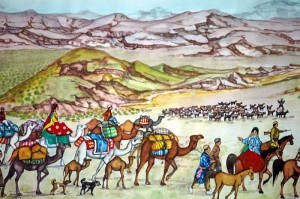

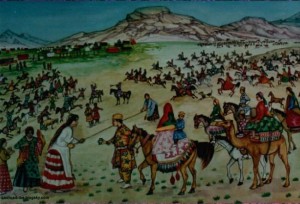

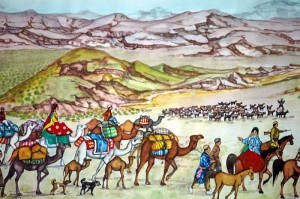

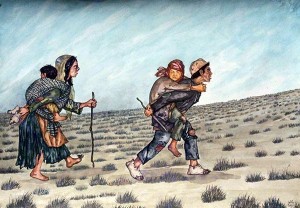

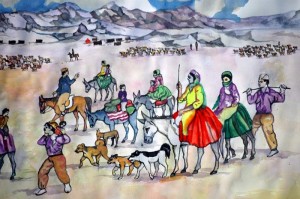

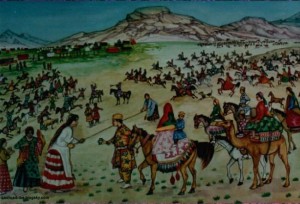

Barth’s fieldwork among the Baseri was limited in time. In the appendix to his book, he pointed to an apparent ritual poverty among the Basseri and a peculiar disconnectedness and irrelevance in the tribe’s impoverished ritual activities (1961:135). In order to take account of the “oddity” of the Basseri case, Barth proposed a reformulated adoption of Leach’s (1956) definition of ritual. In the Leachian (then alternative) approach sacred and profane were regarded as two aspects, rather than two types of actions. On the basis of such a re-examination, Barth brilliantly suggested considering the annual spring migration as the central rite of the Basseri nomadic society.

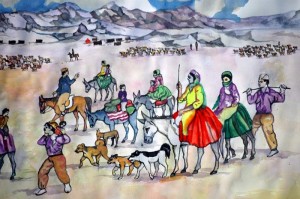

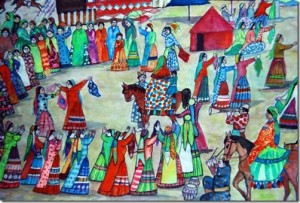

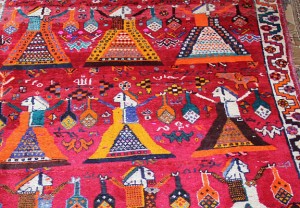

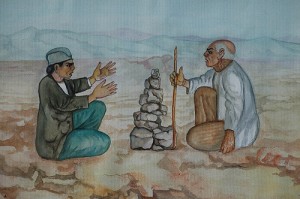

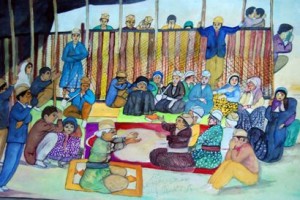

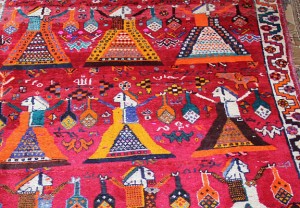

Bijan Bahadori Kashkoli

It should be noted that Barth’s fieldwork among the Baseri was limited in time, and, as such, he was not able to observe the range of ritualized practices among the Basseri.

Works on relations between religious practices and local level political and social structures and processes among Middle Eastern pastoral nomadic groups are limited, and studies of religious discourse among these communities are not extensive. There are, however, a few exceptions.1

Tapper’s study of the Shahsevan of Iranian Azerbaijan (1979) is unique in addressing three less studied aspects of Middle Eastern pastoral nomadic groups:

a) characteristics of grazing rights;

b) structure of local nomadic communities; and

c) rituals.

Tapper aims to analyze the internal and synchronic relations among the above three aspects of the Shahsevan society. He supports Douglas’s (1973) view that the existence of closed social groups, where group boundaries are associated with power and danger, is the most important determinant of bias for ritualism. In support, Tapper characterizes three Sunni groups –the Cyrenaican Bedouin, (Peters 1976), the Al-Murrah Bedouin (Cole 1975), and the Yomut Turkmen (Irons 1975)–, as well as the Shia Shahsevan, as examples of more religiously orthodox Middle Eastern groups that emphasize religious rituals, and identifies them as also having the most corporate local communities.

Not only do the Shahsevan have well defined local communities, but, due to their system of grazing rights, Tapper argues, the internal relations of their communities are more complex than those of similar populations in the Middle East (1979:17).

Tapper’s reading of the Shahsevan ritual scene is unique in another major sense. Among the Shahsevan Tapper finds religious rituals that, in a Durkheimian fashion, define and consolidate groups. His study of Shahsevan public rites is not confined to their Islamic public rituals, it also includes those of an individual’s life-cycle, and the spring migration.

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Tapper describes the Shahsevan as a group whose “public ritual life is unusually rich for a Muslim nomadic society” (1979:176), and argues that the differences between the Shahsevan and the Basseri in this respect are related to differences in social structure. The Basseri, by being able to express and resolve hostilities by change of allegiance from one community to another, are not threatened by structural conflicts. However, among the Shahsevan, where the community is organized on conflicting principles, and residential flexibility is non-existent, hostilities within the community are expressed during the ritual of nomadic migration. But the solidarity of the community is further ritualized by the Ramazan (fasting month) and the (Shia) Muharram rites, which the Shahsevan, unlike the Basseri, observe with enthusiasm (1979:253-54).

The Muharram rites signify the Karbala tragic sacred narrative, in which Imam Hussein, a grandson of the Prophet, and the third Shia Imam, and many of his companions were martyred. Karbala is located in the present day Iraq. Muharram is the first month of the Islamic lunar calendar.

Later, Bradburd (1984a, 1990), based on his studies of the Komachi of Kerman, stated that practice of public religious rituals is more widespread among pastoral nomadic/tribal groups in southwest Asia than previously indicated. He showed how unity, hierarchy, and divisions of the Komachi community are represented in their Muharram and life-cycle rites.

Bradburd’s general remark, that the participation of the area’s pastoral nomadic/tribal groups in Islamic public rituals needs to be (empirically) reevaluated, is well taken. Nevertheless, one could say that in Fars, perhaps somewhat similar to Kerman, Muharram public rituals were more practiced by its (Shia) settled, non-tribal or Tajik population. This could be regarded as one of the ethnic or cultural markers differentiating the settled Tajik (or “Persianized”) urban and under-urban-influence communities from non-Tajik (tribal/nomadic Turk, Lur and Arab-Basseri) backgrounds.

There might be an “ethno-linguistic twist” to participation of the Shahsevan and Komachi nomadic communities in Muharram public rituals. Though the Shahsevan differentiate themselves from non-tribal rural and urban populations, Azerbaijan’s population is, like the Shahsevan, predominantly Turki (Azerbaijani) speaking. In Kerman, too, the Komachi, as Persian speakers, resemble the predominant Persian speaking population of the region.

One could also consider the possibility of Shahsevan’s participation in Muharram rituals during the time of Tapper’s research, among other things, as an effort to claim their Islamic identity in the context of bordering the (then) atheist Soviet Azerbaijan state.

Qashqai and Muharram Public Rituals

Still, it could be said that, generally speaking, during the decades preceding the Islamic revolution of 1978-79, when the above studies by Barth, Tapper and Bradburd were carried out, such rites were more characteristic of the Shahsevan and the Komachi than the Qashqai and the Basseri. And, in the same period in Fars, the Qashqai in general were perhaps more involved in these rites than many of the Lur tribal groups of west of the region, or those of the Arab and the Basseri of the east.

There is a geographical connection. The Qashqai are more centrally located in relation to the major urban centers of the region, than many of the the groups of western and eastern Fars.

It should be emphasized, however, that the Qashqai constitute a complex and differentiated community in many ways, and their religious discourses and practices were, and are, multiple and diverse.

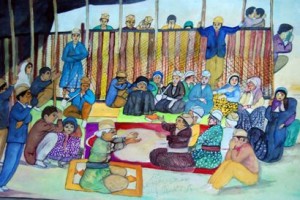

Practicing Muharram public rites varied over time and across different Qashqai communities. Many previously nomadic communities, as they settled, started practicing the rites as they were practiced by the peasants and town dwellers in the region. During the sixties and seventies there were some nomadic Qashqai communities who did organize and participate in Muharram rituals–mainly composed of processions from camp to camp, singing Muharram-related lamentation poetry (noheh) in Turki (Qashqai Turkic), and given food by the camp leaders. These were usually nomadic communities with more contact with settled people.

Again among the variety of factors that could be studied as influencing the practice of Muharram rituals in different Shia pastoral nomadic communities, one could look at a historical connection. The sixteenth century expansion of Shiaism in Iran, and its transformation to the official, the state and the majority faith, was heavily based on conversion and military support of Turkic speaking tribal groups, like so many that were later incorporated into the Qashqai.

The nomadic Qashqai may reason that the scattered pattern of households in pastoral areas, the necessities of pastoralism and nomadism, and their general way of life was such that they did not often hold Muharram public rituals–the way they are practiced by the settled people. There are, however, certain Muharram-related practices which were specific to a nomadic mode of living. Camps refraining from migrating during the two main days of the Muharram rituals (the ninth and the tenth of the month), is an example. And, if the tenth of Muharram (based on a lunar calendar) happened to be the same day that a nomadic camp has to make a migratory move, rather than starting the move very early in the morning, in the customary fashion, the camp postpones its move until “the blades have been drawn,” that is, in the afternoon of the tenth, or after the tragic climax of the sacred narrative of Karbala is over.

Previously many Lur, Turk, and Arab populations in the Fars region who settled took part in such public rituals as part of their process of ethnic transformation (“Tajikization” or “assimilation”). In settled urban and rural areas the expenses of the public rituals were provided by state authorities, merchants, landlords, neighborhood and guild leaders, rural community leaders, by whole communities, or a combination of these. Among those Qashqai communities which did practice in such rites, usually, it was the camp leaders who offered the food and tea. Having a religious vow was part of this patterns of exchange.

The Qashqai, similar to the tribes of eastern and western Fars, consider themselves Shia Muslims, part of the region’s and the country’s Shia community. They venerate Shia saints. Among Shia saints, how they specially revere Hazrat-e Abbas, a brother of Imam Hussein, who is particularly famous for his bravery, to a certain degree, differentiates between their dominant discourse on Shia saints and that of a more urban-based discourse. In this regard, the Qashqai are more similar to other tribal populations in the region.

Another point of qualification also needs to be made. Muharram rituals, as well as discourses on them, took a historically-specific political dimension in the immediate pre-revolutionary period. With the expansion of contemporary radical political discourse(s) on Islam among urban populations during the seventies, Muharram rituals became a major vehicle for, and focus of, mass politics. With the rapidly expanding ties between the urban and non-urban populations during the sixties and seventies, many of the region’s rural and nomadic populations, and especially its youth, also took a new look at these rituals and the ideas they could represent. The (re)emerging discourse on Shia Islam’s revolutionary potentials, popular among the politically engaged youth of the expanding urban centers and educational system, was also communicated among the Qashqai youth. In the post-revolutionary period, with the Islamic state in power, Muharram public rituals have acquired still more complex and changing, but nevertheless telling dimensions and relations with the changing local and larger social context of their performances.

During the post-revolutionary period the Qashqai and other previously tribal groups in the region have intensified their already rapid processes of sedentarization, migration to urban centers, and, for many, acculturation to the changing dominant urban, and state sponsored or supported public Muharram rituals, though in such rituals those (men) who participate represent themselves in the larger urban public spaces as the Qashqai.

Pasture Rights and Community Rituals

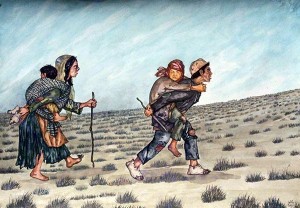

The Qashqai nomadic population was class-based, and its nomadic communities were organized on various principles. Their system of grazing rights was very complex. A variety of patterns according to which grazing rights were controlled, owned, allocated, rented, and exchanged in either summer or winter quarters existed among various Qashqai nomadic communities, and across time.

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

The integrative and conflictual processes within Qashqai local level nomadic communities could not be reduced to the peculiarities of the Qashqai systems of pasture control and the necessities of pastoral nomadism. There is more than one type of Qashqai nomadic community, and forms of pasture ownership and control varied over time and space. The form of pasture control and ownership is not the only factor shaping the type and dynamics of nomadic communities. Control and ownership of other pastoral productive factors–animals and labor–are also important as factors shaping various local level nomadic communities.

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Moreover, if we include semi-settled, and also settled (rural and urban) Qashqai communities in our inquiry–in contrast to solely nomadic cases recorded among the Shahsevan–we encounter a constellation of various structural forms, and of integrative and conflictive processes. Still, our list could be enlarged and take on an added complexity if we include the micro-historical, and possibly macro-historical changes of Qashqai local-level community types. A host of internal as well as external economic, and also political, factors could be discussed as having a role in the dynamics of a given Qashqai local-level community at a given time period. On the whole, it could be said that various forms of solidarity and tension, and multiple forms of domination and cooperation are characteristic of the Qashqai local communities–whether nomadic, semi-nomadic, settled, or, as at present, mixed.

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Bijhan Bahadori Kashkoli

Flexibility and multiplicity of structural forms is a general feature of the Qashqai, but it is not a feature confined to them.2 Social groups are formed and re-formed, some on more and some on less flexible grounds. The point to ask is how communities are ritually enacted, recreated, and communicated.

Rituals are representative as well as reconstructive of social relations and groupings. At least for few decades, the history-making, as opposed to structure-preserving, aspect of rituals have been discussed by anthropologists.3 Ritual or ritualized practices could emphasize conflict, and not necessarily solidarity. Of course, public conflict becomes possible as alliances are formed internal to each of the parties involved. Such alliances could themselves be flexible, or subject to reconstruction. We may ask how social relations and groups are represented and reconstructed in ritualized ways that are central, culturally valued, or elaborated, but may represent or promote conflict and rebellion, in contrast to, or in addition to, integration and compliance.

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

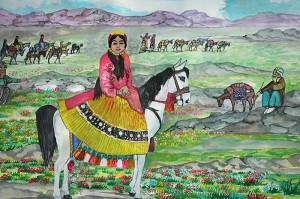

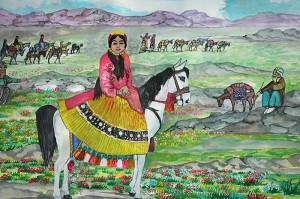

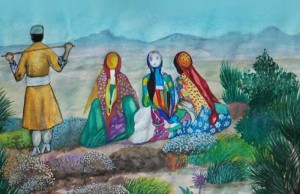

Migrations, life-cycle ceremonies, and, for some, Muharram rites were central to the Qashqai repertoire of public rituals practices.

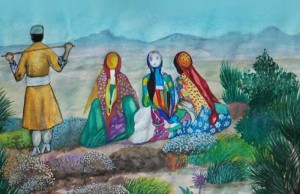

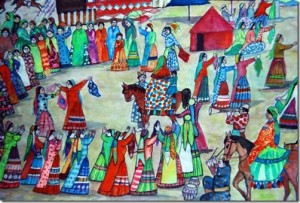

Marriages and Weddings

A marriage marked a reconstruction of relationships between individuals and between local level groups; some marriages involved larger level units. One dominant discourse on marriages regarded it as exchange of women: this individual/group gave/received a woman to/from that individual/group. Giving and receiving wives among tribal leaders was, proportionally, a more significant event. Marriages brought people together. Many marriages were acts of re-alliance: between two sublineages of a larger paternal lineage, or two lineages related to each other through previous marriages but not as a larger patrilineage. Marriages were also performed to make new alliances, changing non-kin to kin. Made to bind and rebind, marriages could also provoke conflict. They brought groups of people together, but they also could be relied upon to differentiate (e.g. status groups, or allies and non-allies). There were rules of marriage: strict marriage taboos (Islamic prohibitions), and preferential rules–preferences for father’s brother’s daughter and other forms of cousin marriage, and status-related rules (one gives women to men of similar status or higher, but not lower).

It has been pointed out that marriage preferential rules are possibilities that can be adducted or ignored (Eickelman 1979, Rosen 1979, Bradburd 1984), and that they are part of the strategic social resources the actors may rely upon to make a “good marriage.” I would like to emphasize, however, that every good marriage, according to some parties, could be potentially regarded as a “bad marriage” by others. In delicate, complex, and flexible series of alliances and counter-alliances at local and regional levels, every (re-)alliance through a new marriage was a reconstruction of micro-level local (or larger level) political make up, and there was always a potential for others to challenge it, or enact their challenge during the wedding.

In a situation where political dynamics was the result of hierarchical, as well as reciprocal relations, a marriage had the possibility of being questioned by others at the higher or the same level of political hierarchy. Marriages involved reconstruction of political, economic and status relations, they brought about fusion, but also, potentially, fission.

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Ritual and Ritualization

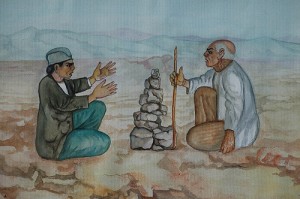

Catherine Bell’s book, Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (1992), put forward a new framework for understanding the nature of ritual. Bell’s insight was that ritual is better understood as strategy, or a culturally strategic way of acting in the world. She covered a host of academic work on defining and studying ritual, and contended that few, if any, of theories of ritual avoid a rather predetermined circularity. This circularity constitutes ritual as an object of analysis in such a way as to mandate a particular method, expertise, and way of knowing. In order to break free of the circularity, she abandoned the focus on ritual as a set of special practices, and put her focus on strategies of “ritualization,” defined as a way of acting that differentiates some acts from others. Ritualization is a form of practice through which a “socialized body” strategically demarcates and privileges the meaning of some acts over others within a “symbolically constituted spatial and temporal environment to achieve a “desired social effect” (1992: 93). By acting ritually, embodied agents “wield physically a scheme of subordination or insubordination” (1992:100).

Thus, practices such as pilgrimage, dividing food at a formal gathering, choosing a place to sit, hunting events of the tribal elite, swearing to affirm that something is the case, or asking for forgiveness, in addition to a host of health-related practices, all could become publicly ritualized, depending on the way they are acted or interpreted as such.

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkuli

Social Dramas and Ritualization

Social dramas should also be added to the list of the major rituals provided by Barth, Tapper, and Bradburd. My emphasis on social dramas as ritual events, and their related ritualized practices, is, among other things, related to a major characteristic of the Qashqai society: flexibility and multiplicity of sociopolitical relations and discourses on them. Groups, identities, and sociopolitical relations are reconstructed, imposed, contested, and negotiated in multiple and flexible ways. They are periodically (re)formed in extra-ordinary dramas of social conflict, but are also perpetually reshaped in ordinary daily activities.

As studies of everyday forms of resistance have shown (e.g., Scott 1990), acting in conflict is not confined to extraordinary times of strife and rebellion. More subtle forms of discord and fighting back are commonplace in daily local-level activities, and ritual plays a major part in these practices, as well. These later major domain(s) of ritualized acts, those that include ordinary or not overtly extraordinary forms of presentation, rejection, and negotiation of identities and relations, are not discussed here. Examples for the Qashqai are variations in attire worn, places offered (or chosen) to sit, gifts exchanged, visits made, food divided and offered, and language used. Of course these could be done or performed as part of a larger ritual, such as a wedding, a mourning, or a feast.

One should also add that during the last few decades, with rapid transformation of Qashqai political structure and cultural practices, and integration of masses of the Qashqai in larger changing national political field, a host of new symbols and discourses related to modern state and civil society are used in daily communications.

Ritualization is an aspect of political conflicts, and Bell’s insights can bring a new light on applying Turner’s ideas about social dramas. Victor Turner in several works (1957, 1967, 1968, and 1974) reflected on social drama as ritual-like processes of political conflict. These occur in small-scale communities, as well as in complex societies. He has analyzed such processes as having a phase structure. These phases are breach, crisis, redress, and either integration or a recognition of schism.

By looking at political conflicts some major aspect of Qashqai socio-political relations and grouping are better appreciated; that they are multiply reconstructed, are flexible, contain conflict as well as consensus, and that they are reconstituted in ritual-like ways. It is interesting to study a given social drama (or a set of interrelated dramas) because it as a whole, and its sub-processes of breach and crisis, discloses and reconstructs the pattern of prevailing struggles, as well as the more underlying, but nevertheless changing sociopolitical characteristics of the political field. In Turner’s words, “conflict seem to bring fundamental aspects of society, normally overlaid by the customs and habits of daily intercourse, into frightening prominence” (1974:35).

Turner’s model of the phase structure of social dramas, however, needs to be modified somewhat. His model is based on rather neatly differentiated phases. But a drama’s phases, necessarily, could not be uniformly distinguished. This could be due to purposeful actions by the agents involved.

Among the Qashqai, for instance, the situation at the every-day practices of the groups and individuals involved could be one of neither reconciliation nor permanent cleavage, but rather a blending of the two. The same groups and individuals could present texts of reconciliation in some contexts and those of cleavage in other. These are texts which could be read as complementary and/or contradictory to each other, communications using creative forms of political and cultural etiquette, where reconciliations are presented and cleavages perpetuated.

Social dramas, in contrast to weddings or religious rites, have a much higher degree of improvisational possibilities. When a drama is characterized by complexity and multiplicity of groups, individuals, and voices, and when there are a variety of public and private stages, there could be various interpretations of the drama itself and its phases. Furthermore, there are inter-mingling of dramas, and there are dramas within dramas.

During the liminal period between the Monarchic and Islamic regimes, for instance, the Qashqai were involved, as agents and active and critical viewers, in a variety of intertwined local, regional, and national dramas. Dramas could be mixed at the same level, for instance those of two local communities. And, as local or regional dramas that also deal with larger national issues, they could be mixed vertically.

The importance given to social dramas here is also a reflection of the importance given to conflicts in narratives gathered among the Qashqai and throughout the region. Narratives of social dramas are a major mechanism by which people remember and reconstitute their past, as well as reconstruct their present. Narratives of social dramas provide a vehicle for the construction, dissemination and negotiation of historical knowledge. Narratives of social dramas, parts and pieces of dramas, or allusions to dramas, constitute some everyday forms of political practice regarding local as well as larger regional and national concerns. Political imageries are made when historical imageries are presented. Through the course of social dramas, and by telling of their narratives, tribal, ethnic, and national communities and identities are reconstructed anew.

Bijan Bahadori Kashkoli

Bijan Bahadori Kashkoli

Social dramas share a certain similarity with other types of rituals: ritualized, representative, or socially communicative movements between times, political, cultural, social, and spatial categories create meaning and reconstruct social relations. The idea dates back to van Gennep’s seminal work on rites of passage (1960), but it has been developed by Turner in his various works on rites of passage as well as on pilgrimages (for instance, Turner 1974).

Anderson (1983:55-57) has pointed out how journeys of state functionaries in the absolutist state apparatus in Europe helped to create a model of the state different from the previous feudal states. And Geertz (1983) has described the symbolism of campaigns, or symbolic movements in space, by political leaders in Morocco, England, and Java as meaning creating practices. Various authors have also reflected on the creative aspects of pilgrimages and migrations by Muslim travelers (Eickelman and Piscatori 1990). Movements between socio-spatial and politico-cultural categories by individuals and groups in the course of social dramas could be underscored in terms of their ritualistic aspect as well.

Other rituals could become extremely potent events when they are enacted during social dramas. A marriage ceremony could itself become a dramatic event, or a phase of a social drama between two groups. A marriage could also become the final act of a peaceful resolution of a social drama.

Another example is the social drama of the revolutionary years of 1978-79, during which Muharram rituals were reconstructed in particularly forceful, dynamic, and persuasive, yet multiple ways.

During years of the liminal period between the rules of the monarchic and the Islamic states, local and regional dramas that constructed and contested social class, tribal, ethnic, and political identities were variously interwoven with the larger national revolutionary drama.

In sum, I argue that, based on ideas of Turner and Bell, conflicts among the Qashqai (and similar groups in the Fars region) should be added to their list or repertoire of major rituals, by studying them as social dramas, or ritualized practices, through which various forms of tribal, ethnic, national, class, and gender identities are constructed, imposed, resisted, negotiated, and reconstructed. The handwritten text on the history of the Qashqai (A Qashqai Historigraphy) contains plenty of examples of social dramas (within the Qashqai and between the Qashai and the state or/and other tribal groups). Some of the dramas the occurred during the liminal revolutionary period of late 1970s and early 1980s had strong class identity construction aspects.

*****

* The first draft of this article was written for a seminar on ritual and power I took with Simon Ottenberg in Seattle in 1990. I would like to thank him and Steve Harrell, my othe professor in Seattle, as well as my first anthropology professor in the early 1970s in Shiraz, Bruce Livingston, who was a student of Victor Turner in Chicago.

NOTES

1 – Tapper (1979) gives a short review of this limited literature. Major examples are Barth/Pehrson (Pehrson 1966), Cole (1975), Peters (1976). Tapper (1979) and Bradburd (1984a, 1990) have specifically dealt with the subject among Iranian Shia tribal/nomadic groups.

2 – Based on my historical and short ethnographic studies of some other tribal populations in the region, and some other parts of Iran, I would say that such structural flexibility and multiplicity is a widespread feature of many Iranian pastoral nomadic/tribal populations. A close look at historical sources also point to structural flexibility and multiplicity of tribal populations throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia.

3 – Constitutive or constructive aspects of rituals were shown in studies by the Manchester school of social anthropology (Turner, Gluckman, et al.). Some other earlier studies in this respect are Kertzer 1974, Cohen 1977, and Moore and Myerhoff 1977. Recent genre of studies known as the anthropology of resistance, and contemporary works on verbal arts, rituals, and other forms of expressive culture which look at such practices in terms of their combined semantic-pragmatic or representative-constitutive characteristics, emphasize the constructive or history making aspect of ritual-like practices.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict

1983 Imagined Communities: Reflection on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. Verso. (Revised Ed. 1991)

Barth, Fredrick

1961 Nomads of South Persia: the Basseri Tribe of the Khamseh Confederacy. Uniersitetsvorlaget.

Beeman, William O. 1993 The Anthropology of Theater and Spectacle. Annual Review of Anthropology. Vol. 22: 369-393.

Bell, Catherine M. 1992 Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford University Press.

Bradburd, Daniel

1984a Ritual and Southwest Asian Pastoralists: Implications of the Komachi Case. Journal of Anthropological Research 40:380-393.

1984b The Rules and the Game: The Practice of Komachi Marriage. American Ethnologist 11(4):738-53.

1990 Ambiguous Relations: Kin, Class, and Conflict among Komachi Pastoralists. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Cohen, Abner

1977 Two-Dimensional Man: An Essay on the Anthropology of Power and Symbolism in Complex Society. Tavistock.

Cole, Donald

1975 Nomads of the Nomads. The Al Murrah Bedouin of the Empty Quarter. Aldine.

Douglas, Mary

1973(1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Rutledge.

Eickelman, Dale and James Piscatori (eds.)

1990 Muslim Travelers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination. University of California Press.

Geertz, Clifford

1983 Centers, Kings, and Charisma: Reflections on the Symbolics of Power. In Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. Clifford Geertz. Pp. 121-146. Basic Books.

Gennep, Arnold van 1960 The Rites of Passage. Chicago University Press.

Irons, William

1975 The Yomut Turkmen: A Study of Social Organization among a Central Asian Turkic- Speaking Population. University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

Kertzer, David

1974 Politics and Ritual: The Communist Festa in Italy. Anthropological Quarterly 47:374-389.

Leach, Edmund

1964 (1956) Political Systems of Highland Burma. Beacon Press.

Myerhoff, Barbara G. and Sally Falk Moore (eds.)

1977 Symbol and Politics in Communal Ideology: Cases and Questions. Cornell University Press.

Pehrson, Robert N.

1966 The social organization of the Marri Baluch. (Compiled and analyzed from his notes by Fredrik Barth). Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research.

Peters, Emrys L.

1967 Some Structural Aspects of the Feud among the Camel-herding Bedouin of Cyrenaica. Africa 37:261-282.

Rosen, Lawrence

1979 Social Identity and Points of Attachment: Approaches to Social Organization. In Clifford Geertz/ Hildred Geertz/ Lawrence Rosen (eds.) Meaning and Order in Moroccan Society. Cambridge University Press. 1-122.

Scott, James

1990 Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. Yale University Press.

Tapper, Richard

1979 Pasture and Politics. Economics, Conflict and Ritual among Shahsevan Nomads of Northwestern Iran. Academic Press.

Turner, Victor

1957 Schism and continuity in an African society: A study of Ndembu village life. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 1967 The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

1968 The drums of affliction A study of religious processes among the Ndembu of Zambia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

1974 Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Cornell University Press.

1980 Social Dramas and Stories about Them. Critical Inquiry. 7(1): 141-168.

1982 From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. PAJ Publications.

Hossein Bahadori Kashkoli

Hossein Bahadori Kashkoli